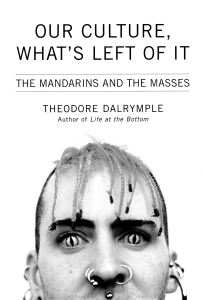

Art as a kindergarten activity for adults who want to feel special

Art as a kindergarten activity for adults who want to feel special

Ambling through the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter, Dalrymple notices that an exhibition, called Happiness 17, is being staged by students of the National High School of Fine Arts. Hopefully, he drops in; but favourable his impression is not — far from it. He writes:

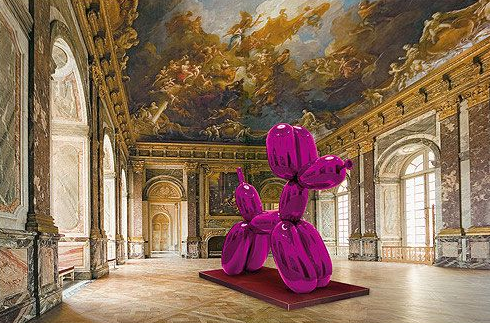

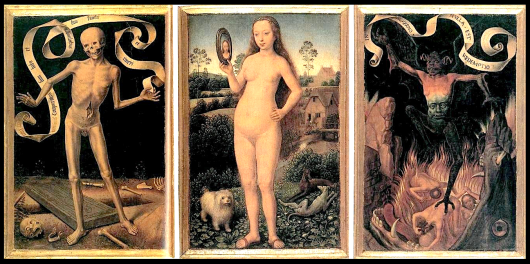

If anyone should want evidence of the collapse of the Western artistic tradition, he could do worse than to go to the annual exhibition of the graduates of the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris. No city in the world is more saturated with that tradition than Paris, and therefore in no city is the collapse more painfully obvious.

Entry to the exhibition is free of charge,

but even so, not many people take the trouble to enter, not even the schizophrenics cared for in the community or homeless Syrian migrant families (actually, mainly Albanians) who hold out paper cups to passers-by for alms.

The ‘art’, Dalrymple says,

is too painful to be endured, even by them; the discomfort of inclement weather is nothing in comparison to that occasioned by the products of modern art teaching and theory.

it is not globalisation that has produced this effect upon artistic judgment; the rot is internal to the art world itself, as has been the rot in the humanities departments of our universities.

He points out that

the loss of belief that there is anything sub specie æternitatis has rendered art trivial, no more than a kindergarten activity for adults who want to feel special and whose thirst for self-expression is greater than anything they have to express. Moral and æsthetic capital is not expended all at once, but gradually; it is run down steadily until none remains. As Felicità 17 demonstrates, none remains.