Out of her mind

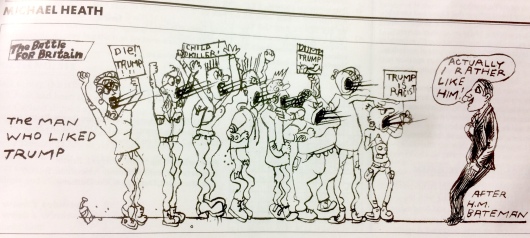

A totally unhinged colleague of Dalrymple’s in the profession of psychiatry called Bandy Lee has branded the American president a mass murderer. Dalrymple responds with the observation that while Donald J. Trump has certain deficiencies of character (don’t we all?) and is not, perhaps, the sort of person one would invite to dinner, he

has bombed no foreign countries; nor has he called out troops and instructed them to mow down citizens in the street. True, he is not an emollient man, but that is not the same as being a mass killer.

Trump has driven Lee nuts. She wants him locked up. She has tweeted about him something like 9,000 times. She is utterly obsessed by him. She

warned against the dangers he posed to the world from before his election, in the manner of old-fashioned preachers who used to warn their congregation of the eternal hellfire to come if they masturbated. (Physicians were more moderate. They warned only of blindness and mental debility.)

But Trump has let her down.

He has not blown the world up. Indeed, he has been rather isolationist, more eager to repatriate troops than to send them out to desert sands in the attempt to turn immemorial tyrannies into democracies. The number of American military deaths in the last four years has been lamentably low, from the point of view of Dr Lee’s predictions.

An attempt to invalidate the political opinions and choices of opponents on spurious, potentially dictatorial, psychiatric grounds

An attempt to invalidate the political opinions and choices of opponents on spurious, potentially dictatorial, psychiatric grounds